Thuistezien 296 — 06.01.2022

Gregor Schneider

Tote Räume

Tote Räume

In the late summer of 2020, during which we recovered from the first of (what was going to be) a series of lockdowns, West Den Haag opened its doors to the public with a voluminous exhibition covering no less than three floors in the old United States embassy building. The name of the exhibition was ‘Tote Räume’, a retrospective of the German artist Gregor Schneider. From the mundane, small old office rooms on the second floor to the eerie and suspenseful basement, the placement of Schneider’s works corresponded with the embassy rooms exemplary. The brutalist building, the rooms, and the presence of Schneider’s works were consolidated into an immersive experience. Many would agree that the building was made for Schneider. As a result of the second hard lockdown in the Netherlands however, West was forced to close its doors to the public once again.

Yet, Schneider’s works remained in the building. For four months, West had an exhibition without visitors, and ‘Tote Räume’ gained new meanings. The embassy rooms did, indeed, become more lifeless. Shortly after the human-empty finissage of the exhibition, a publication was released, consisting of essays responding to the ‘unheimlich’ work of Schneider. The essays are written by four contributors, namely Andrew Berardini, Ory Dessau, Drew Hammond, and Yael Keijzer and the publication is introduced with a foreword by Marie-José Sondeijker.

With the exhibition at West as a starting point, Ory Dessau’s essay ‘Gregor Schneider: Politics, Religion, History’ engages in the artistic oeuvre of Schneider by placing the works in connection with their implicit historical and political references. As argued in the text, Schneider manages with his works, such as ‘Darkroom’, to materialize displaced segments of historical as well as present-day realities in Europe and the United States. In ‘Notes on Gregor Schneider’s ‘Tote Räume’ at West Den Haag, 2021’, Drew Hammond, investigates the space itself, both in connection with the particularity of the embassy space but also the space’s influence in Schneider’s art. In ‘Tote Räume’, the embassy becomes a sort of readymade as Schneider does not need to intervene with the building’s structure and longstanding function. In the structure of the building’s brutalist architecture there are already ‘dead spaces’. The dead spaces are discussed at length in Yael Keijzer’s essay ‘The Spirituality of Dead Spaces’. She notes that the experience of Schneider’s work lies more in the possibility of imagination than in the material reality. The experience, in this sense, uses the space as catalysts for possibility of fear and anxiety - bordering between actuality and virtuality. Visitors are, first of all, always confronted with their own imagination of what is and what will be in, and in-between spaces. The last essay ‘Travels in Tote Stadt: On the Work of Gregor Schneider’ by Andrew Beradini imagines the combination of Schneider’s work as a city, a city that somewhat resembles the place we are all too familiar with. But in Tote Stadt, the subtle changes that disturb the normal open up an awareness of a hidden, much darker reality that is nonetheless more ‘real’ than the comforting reality we know.

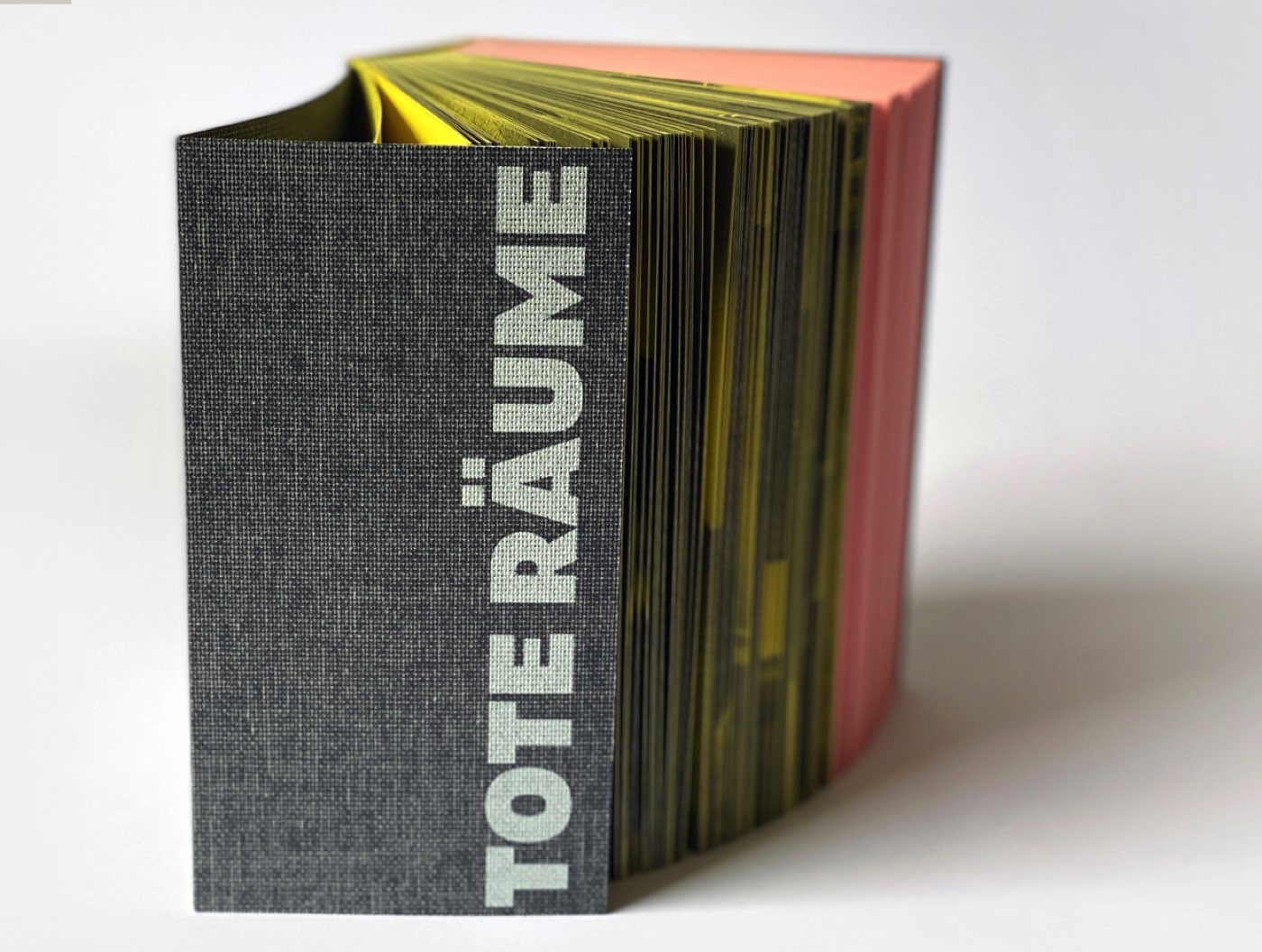

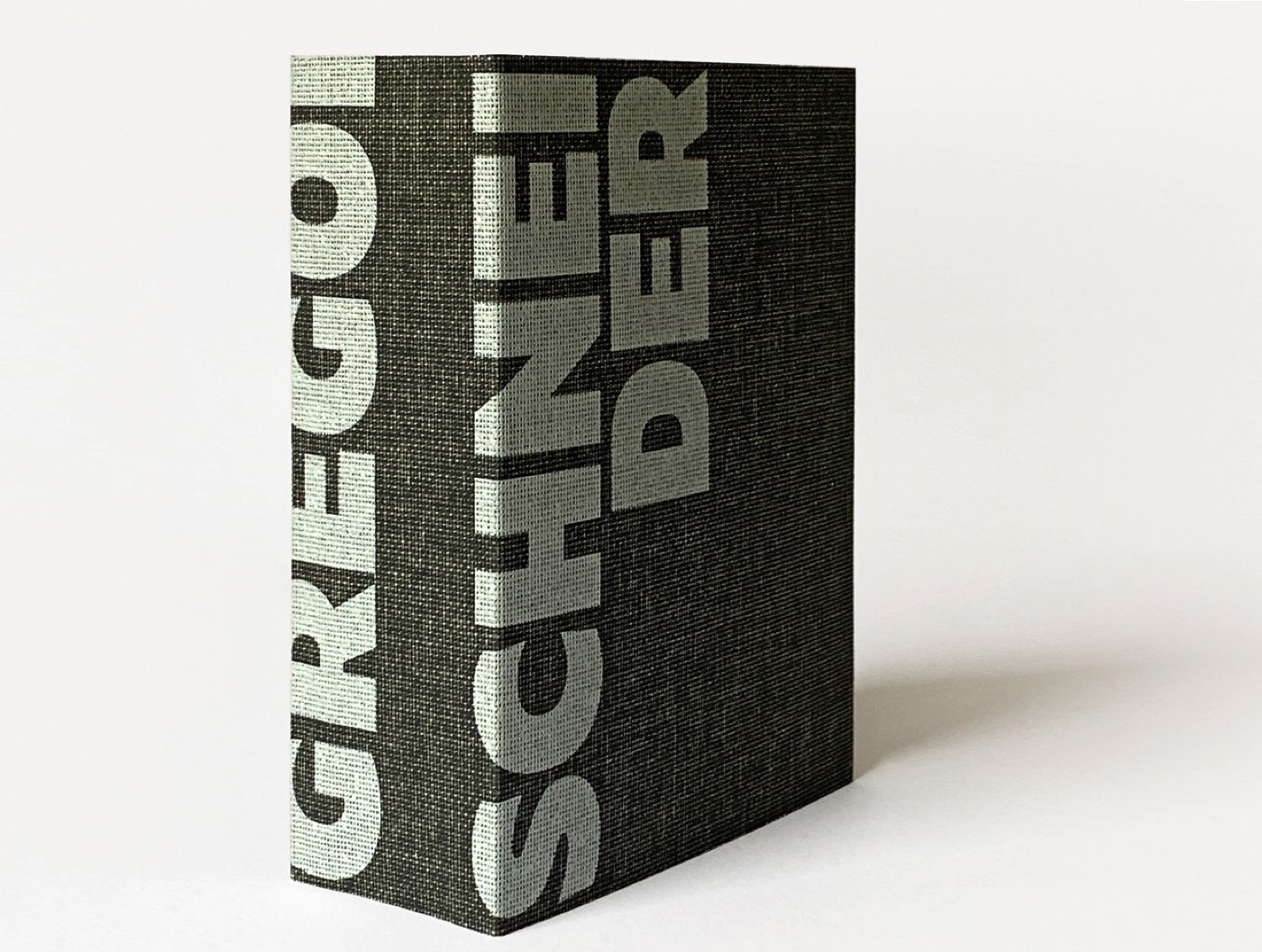

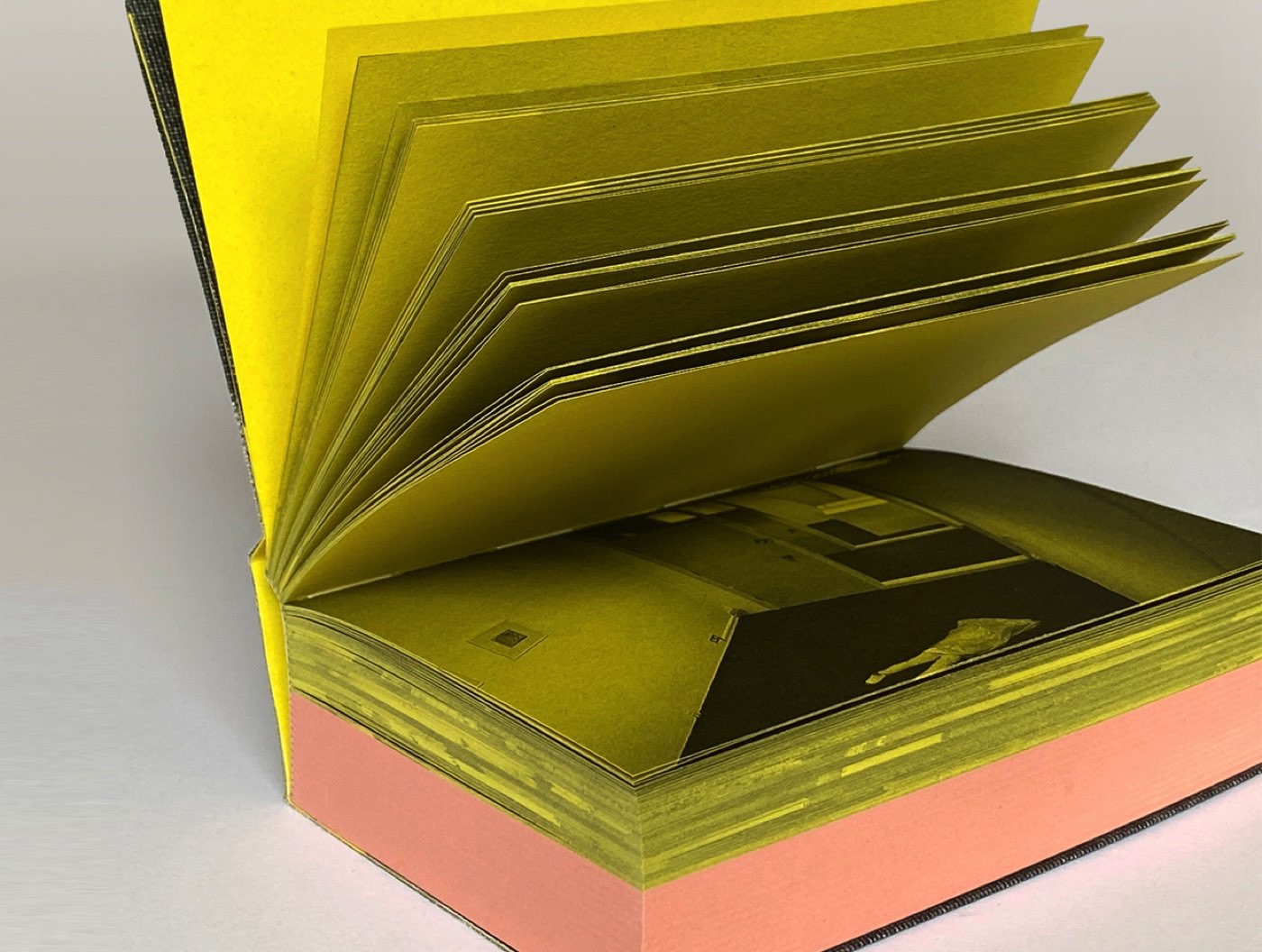

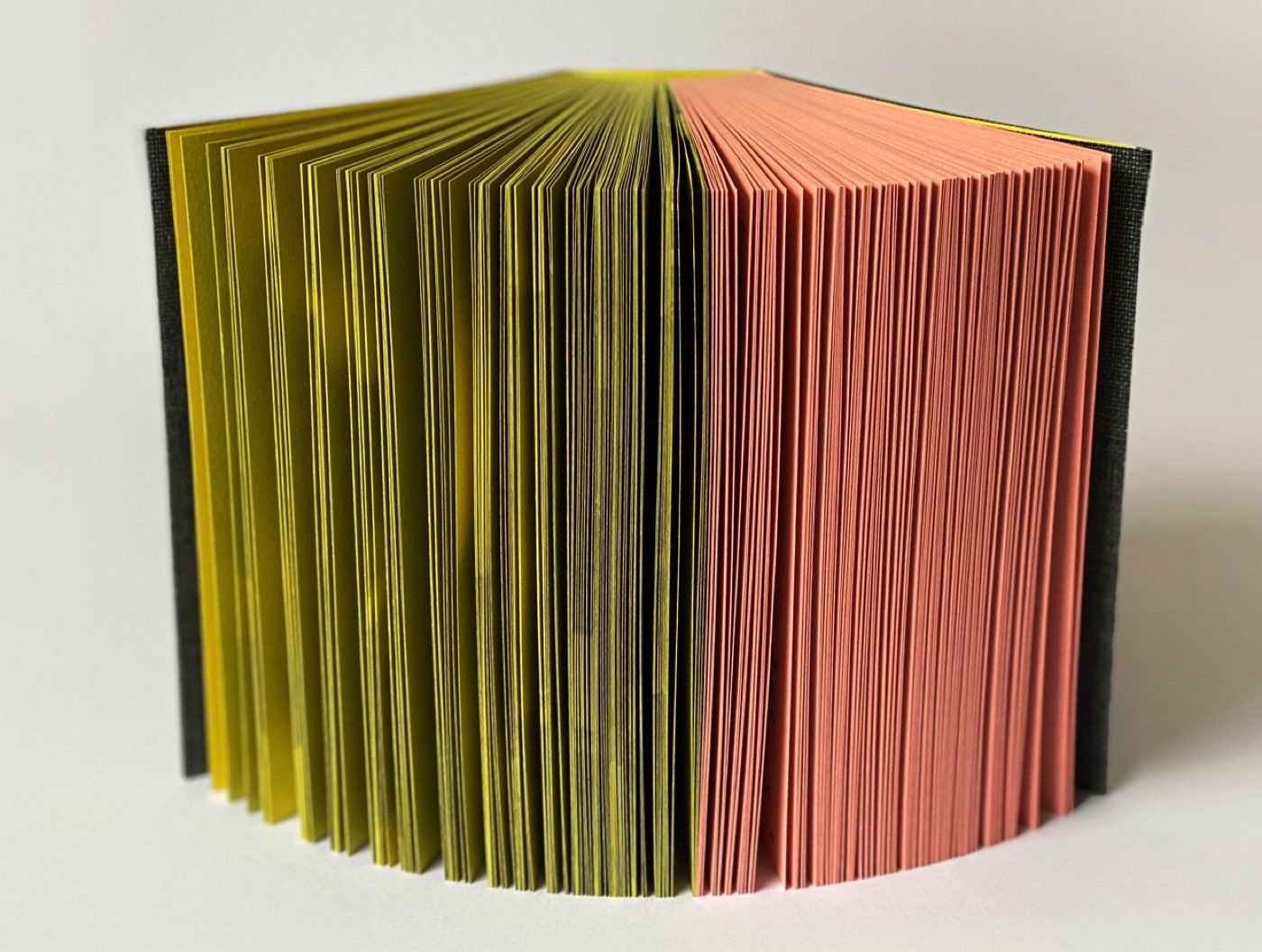

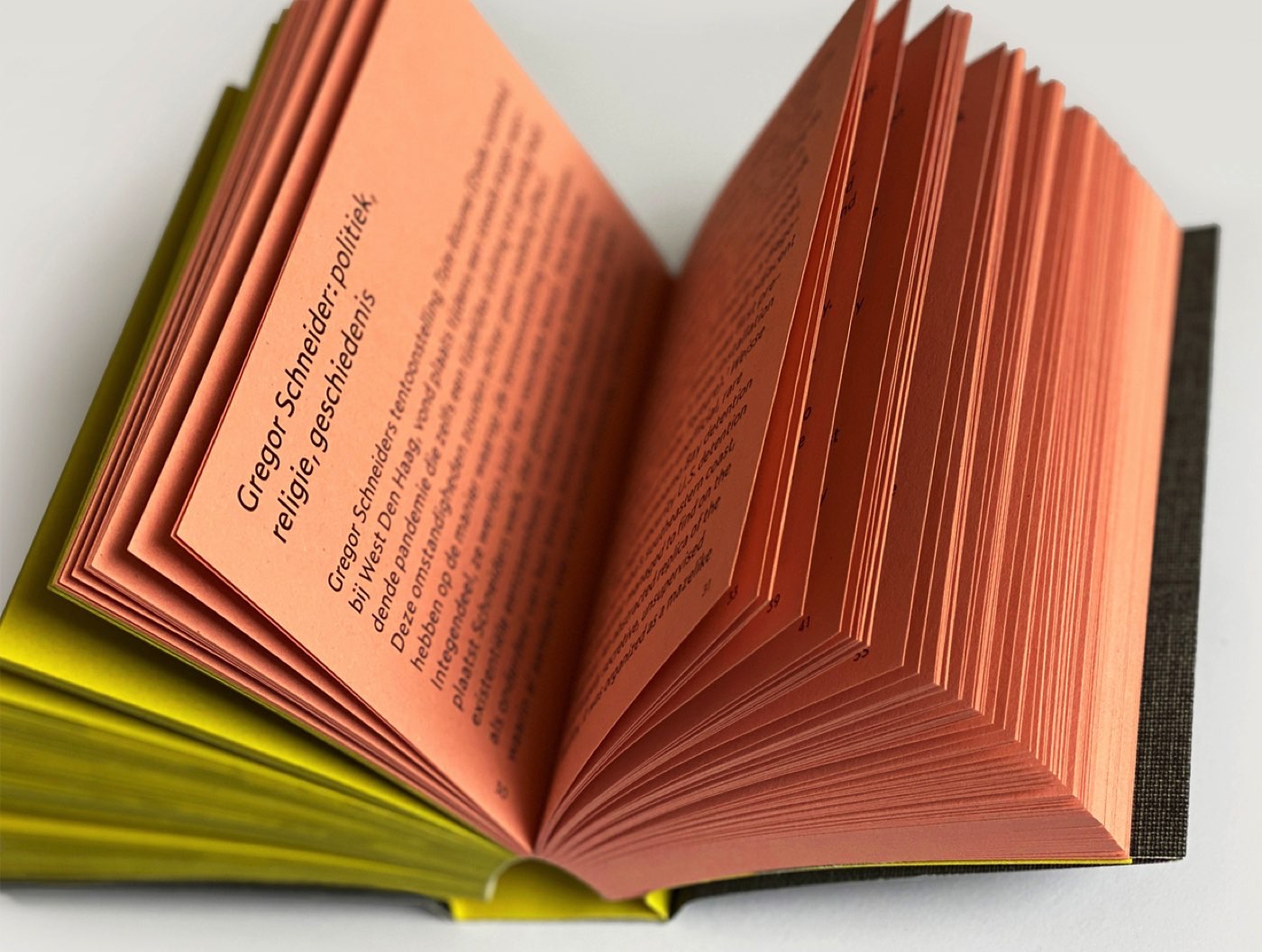

Compact and dense, the book itself resembles the atmosphere of a Schneider room. The first half of the book is a series of stills from a day in the exhibition during the lockdown, recorded by a surveillance cameras. This is not a typical way of documenting an exhibition but, then again, ‘Tote Räume’ was exhibited in a non-typical time.

The catalogue ’Tote Räume’ by Gregor Schneider is available for 25 euro here.

Text: Rosa Zangenberg

Yet, Schneider’s works remained in the building. For four months, West had an exhibition without visitors, and ‘Tote Räume’ gained new meanings. The embassy rooms did, indeed, become more lifeless. Shortly after the human-empty finissage of the exhibition, a publication was released, consisting of essays responding to the ‘unheimlich’ work of Schneider. The essays are written by four contributors, namely Andrew Berardini, Ory Dessau, Drew Hammond, and Yael Keijzer and the publication is introduced with a foreword by Marie-José Sondeijker.

With the exhibition at West as a starting point, Ory Dessau’s essay ‘Gregor Schneider: Politics, Religion, History’ engages in the artistic oeuvre of Schneider by placing the works in connection with their implicit historical and political references. As argued in the text, Schneider manages with his works, such as ‘Darkroom’, to materialize displaced segments of historical as well as present-day realities in Europe and the United States. In ‘Notes on Gregor Schneider’s ‘Tote Räume’ at West Den Haag, 2021’, Drew Hammond, investigates the space itself, both in connection with the particularity of the embassy space but also the space’s influence in Schneider’s art. In ‘Tote Räume’, the embassy becomes a sort of readymade as Schneider does not need to intervene with the building’s structure and longstanding function. In the structure of the building’s brutalist architecture there are already ‘dead spaces’. The dead spaces are discussed at length in Yael Keijzer’s essay ‘The Spirituality of Dead Spaces’. She notes that the experience of Schneider’s work lies more in the possibility of imagination than in the material reality. The experience, in this sense, uses the space as catalysts for possibility of fear and anxiety - bordering between actuality and virtuality. Visitors are, first of all, always confronted with their own imagination of what is and what will be in, and in-between spaces. The last essay ‘Travels in Tote Stadt: On the Work of Gregor Schneider’ by Andrew Beradini imagines the combination of Schneider’s work as a city, a city that somewhat resembles the place we are all too familiar with. But in Tote Stadt, the subtle changes that disturb the normal open up an awareness of a hidden, much darker reality that is nonetheless more ‘real’ than the comforting reality we know.

Compact and dense, the book itself resembles the atmosphere of a Schneider room. The first half of the book is a series of stills from a day in the exhibition during the lockdown, recorded by a surveillance cameras. This is not a typical way of documenting an exhibition but, then again, ‘Tote Räume’ was exhibited in a non-typical time.

The catalogue ’Tote Räume’ by Gregor Schneider is available for 25 euro here.

Text: Rosa Zangenberg

previous

previous next

next